Building Secure Collaboration: MindLink + Pexip Integration Hackathon

In a world where collaboration happens across borders, agencies, and networks, one thing remains constant: the need for trust. At MindLink, we’ve...

7 min read

Harp Gosal : Jun 14, 2022 4:03:36 PM

In the first part of a wider series of blog posts, we examine the world of coalition communication and collaboration in the Intelligence Community. To introduce the series we will be looking at who is part of this community and what tools do they use to disseminate intelligence between coalition partners. Later on in the series, we will identify the challenges and key requirements to deliver secure intelligence sharing between coalition partners. Finally we discuss our approach towards solving these problems and the future of collaboration tools in a coalition-wide C4ISR strategy. Stay tuned for more, but for now, we hope you enjoy part one.

The Security, Intelligence Community (IC) and the military work hand-in-hand to keep their nation safe. Each branch of the military has its own intelligence element, which is both part of the military and part of the IC. Together, these military and civilian IC elements collect strategic and tactical intelligence that supports military operations and planning, personnel security in war zones and elsewhere, and anti-terrorism efforts. Technology systems and data that is collected through collaboration are a powerhouse to facilitating intelligence operations. Naturally, core IC systems need to be secure against adversaries and cyber-attacks which, are becoming more prevalent year on year.

In this article, we will examine what an IC coalition consists of – organizations and partners that disseminate intelligence, and introduce the communication and collaboration tools that facilitate the sharing of intelligence.

First off, what does the IC consist of?

The IC consists of nine Department of Defense elements—

The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA),

The National Security Agency (NSA),

The National Geospatial- Intelligence Agency (NGA),

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO),

And intelligence elements of the five DoD services: the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Space Force.

Within the United States (U.S.), the IC will generally share intelligence or make information accessible across each organization utilizing a number of different mediums. The IC can also expand its intelligence gathering and sharing, leaning on other entities and sources, for example:

Information-sharing relationships between the IC and state and local entities take many forms. A number of formal mechanisms exist to analyze, use, and disseminate information and intelligence in a way that is most useful to individual entities. For example, the Homeland Security and Law Enforcement Partners Board informs senior IC officials and key federal partners on the information needs and challenges facing state and local customers and communities. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Criminal Intelligence Coordinating Council: composed of federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial government partners who convene regularly to identify and prioritize critical issues that can be addressed through improved intelligence and information-sharing.

In addition, FBI-sponsored Joint Terrorism Task Forces have been created in order to widen the breadth of the FBI’s surveillance. Information-sharing between intelligence bodies and law enforcement is facilitated through online information-sharing tools such as Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal and Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS) .

Contact between military intelligence officers and their foreign military counterparts is critical to force protection and overall national security, particularly when conducting joint maneuvers on foreign soil and dealing with international threats. These relationships fill in information gaps, increase operational awareness, and improve understanding of local attitudes and tensions, particularly in areas where cultural complexities and norms are not well-understood by U.S. personnel. At times, other countries have access to information that the country may not. The U.S. also works with other countries to collect and share information on transnational issues that affect all parties: such as terrorism, cybercrime, drug trafficking, and weapons proliferation. These relationships are mutually beneficial to better pursue mutual threats.

Perhaps the longest-lasting intelligence collaboration is with the "Five Eyes" group: comprised of the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The alliance developed out of World War II-era agreements between the U.K. and U.S. to share signals and intelligence, and has evolved into a broader undertaking. In 1955, the arrangement was extended to Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Cooperation among the Five Eyes has provided the U.S. with significant intelligence benefits in all mission areas: counterterrorism, counter proliferation, cyber, regional challenges, and global coverage.

The Intelligence Science & Technology Partnership (In-STeP) program identifies science and technology needs across the IC and examines how those needs can be met by private-sector partners. Another program, the Intelligence Ventures in Exploratory Science & Technology (In-VEST), acts as the catalyst for accelerating private sector research and development (R&D) activities to meet select In-STeP-identified challenges. In-VEST alerts industry and academia to the types of technology the IC anticipates requiring in the coming years so they can invest appropriately now.

The Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) invests in high-risk/high-payoff research to provide the U.S. with an overwhelming intelligence advantage. As the only research organization within the ODNI, IARPA works with the other 16 IC elements to address the IC’s most challenging problems that can be solved with science and technology.

IARPA performs no research in-house. Rather, it funds researchers in colleges, universities, companies, National Labs, and other organizations. IARPA invests in fields as diverse as artificial intelligence, asset validation and identity intelligence, bio-security, chemical detection, cyber security, high performance computing, human judgment, linguistics, radio frequency geolocation, and secure manufacturing of microelectronics.

Finally, within the Cybersecurity domain, the IC and private Cybersecurity companies will coordinate and share intelligence data. Cybersecurity organizations collect intelligence from cyber-attacks and incidents that have occurred across Federal, private and global customers. Some of this information may not be readily available to the IC.

IC, National Security and Cybersecurity draw parallels and are inter-woven. Cybersecurity is an industry domain which falls under the umbrella of the IC / National Security. The definition of National Security, or National Defence, “is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military attack, national security is widely understood to include also non-military dimensions, including the security from terrorism, minimization of crime, economic security, energy security, environmental security, food security, and Cybersecurity.”1

We will revisit the topic of Cybersecurity and coalition communication and how this interlinks back to the IC in a future article.

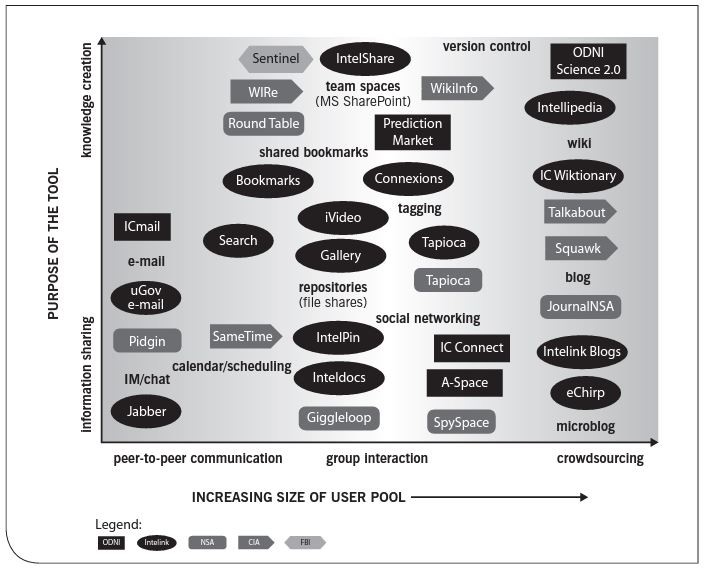

Gregory Treverton at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) conducted a study and produced a report on collaborative and communication tools used throughout the IC2. Treverton analyzed a number of chat, communication and collaboration systems that were built and utilized across agencies and departments within the IC. Treverton’s report found that, the process of adopting collaborative tools has been bottom up. Individual officers began using the tools because they found them intriguing and useful. Well-funded budgets provided money and means to create many in-house and bespoke collaboration and chat tools. Some interlocutors encouraged agencies to do their own thing, creating their own tools rather than collaborating in the process of creating wider collaborative tools. Majority of these purpose built systems are all hosted on-premises or within a secure private cloud cut-off from access beyond the perimeter. Treverton notes that what does not yet exist is a strategic view from the perspective of the IC Enterprise, neither a central architecture nor much attention by senior agency staff to what kinds of incentives to provide for what kinds of collaboration.

Treverton states that communication and collaboration tools fall into two broader categories:

The first category is the best-used chat and collaboration systems within agencies, residing on the particular agency’s server (on-premises) and thus generally inaccessible to anyone in another intelligence agency. They are mostly instant messaging (IM) tools and therefore better at conducting peer-to-peer communications. However, these tools generally do include some chat and other more widely collaborative functions.

The second category is tools used across agencies: the Intelink set which, includes a range of collaborative tools and social media.

Based on Treverton’s findings and report, the best intelligence gathering practices coupled with the capabilities of these communication and collaboration tools in the IC can be grouped and described as below:

Discover: For example, NSA’s Tapioca Neighborhood function, which locates expertise. IM and blogging also can aid discovery. Even chat can cover a range of purposes - from pure logistics, to mundane discovery (When is the meeting?) to more substantive discovery (Who knows about x or y?). Blogs can range from curating (setting down ideas for further analysis later), to crowdsourcing (by inviting others to critique an idea or argument), to discovery (by seeing who responds to a blog or asking a question).

Curating, reference, and research: Tools such as Intellipedia. Like Wikipedia, it contains pages arranged by topic, which officers can add to or edit, with all the metadata available. Agents and Officers also have their own Web pages on Intellipedia. It is a useful living reference for fluid intelligence.

Managing: Principal tools are IM, chatrooms and blogs, and most of the managing is done through agency-specific tools, for most agencies have their own internal chats and blogs. In principle, Intelink chat and blogs could be used to manage projects - from analysis to development, across agencies. Tapioca which is a social networking and collaboration tool, allows the NSA to make information available to its Five Eyes international partners.

Producing original content: This has been the ambition for several tools, notably A-Space and Intellipedia. Intellipedia’s stakeholders regret that the association with Wikipedia induces users to think of Intellipedia only as a living encyclopaedia, not a forum for producing original content. And A-Space (now called i-Space), is valued more for its discovery function, helping analysts with convergent interests.

Outreach: WIRe (World Intelligence Review), is the CIA’s daily “publication” that is no longer published in hard copy, only available online. WIRe uses collaborative tools for outreach. For instance, feeds on eChirp (microblogging) are based on topical groups, and provide notice of thought-provoking or special items.

Source: CSIS Study Collaborative Tools in IC, Treverton

Microblogging tools, such as eChirp, further enable discovery of relevant contacts and sharing of ideas. Such tools also support secure peer-to-peer communication. Social tools that span across IC functions, such as Tapioca, hold the potential to increase the ease with which users can discover relevant contacts. Finally, Intelink Search, while not strictly social-media, plays a role in discovery of social-media content, such as individual “chirps,” which have a unique URL. Social-medial can play a role in substantive collaboration by fostering analysis and dissemination of intelligence. Blogs within agencies and security levels, such as JournalNSA, Talkabout (CIA), and Intelink Blogs, encourage content creation and fluid sharing of information that fosters collaborative analysis, which can ultimately contribute to producing intelligence. Tagging of documents reveals temporal trends (Connexions) in tracking intelligence targets. Graph based technology is a useful tool for managing and manipulating temporal data – commonly used by Cybersecurity organizations. Other tools help in assessing topics and raise questions of priority, while still others generate predictions (Prediction Market) that may benefit analysis. Intellipedia, have the potential to contribute most directly to the production of an intelligence product by demonstrating the potential for open collaboration in producing content.

ICMail, UGov Email, and commercial-off the shelf products such as SAFEmail deliver a secure interoperable communication process across the entire messaging environment, making these ideal solutions for use in the complex, modern coalition military operations environment. SAFEmail is regarded to be a fully capable Military Message Handling System, it also fully adheres to NATO and international communications standards.

So we can see that the IC is a very complex and meticulous coalition of organizations all collecting and sharing very highly sensitive information which, in some situations must be shareable in real-time. Time-sensitivity is crucial - the right information must reach the right groups and people at the right time. From the discussion above, there appears to be a number of bespoke chat and communication solutions that have been utilized across the IC and its agencies. These chat and collaboration systems facilitate the information collecting and sharing process. Commercial off the shelf products such as Microsoft Teams have started to make a break through across approved and secure Government cloud host offerings. But it is my opinion that this transition maybe slow or a reluctant one for many agencies and organizations across the IC coalition. It will be interesting to see how the IC adapts to the increased pace of technology change and the increased demand of information sharing and collaboration as we head into the future. In future articles, we will delve deeper and examine other IC industries and organizations, the impact of change, and how they utilize and manage communication and collaboration across a coalition of groups and people when conducting intelligence operations.

References

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_security

2 Collaborative Tools in the Intelligence Community by Gregory Treverton, CSIS Communication and Collaboration amongst Coalitions within the Intelligence Community

In a world where collaboration happens across borders, agencies, and networks, one thing remains constant: the need for trust. At MindLink, we’ve...

Introduction In the first edition of BrainSync, a new series where we discuss a variety of technical topics we sat down with our CTO, Luke Terry, to...

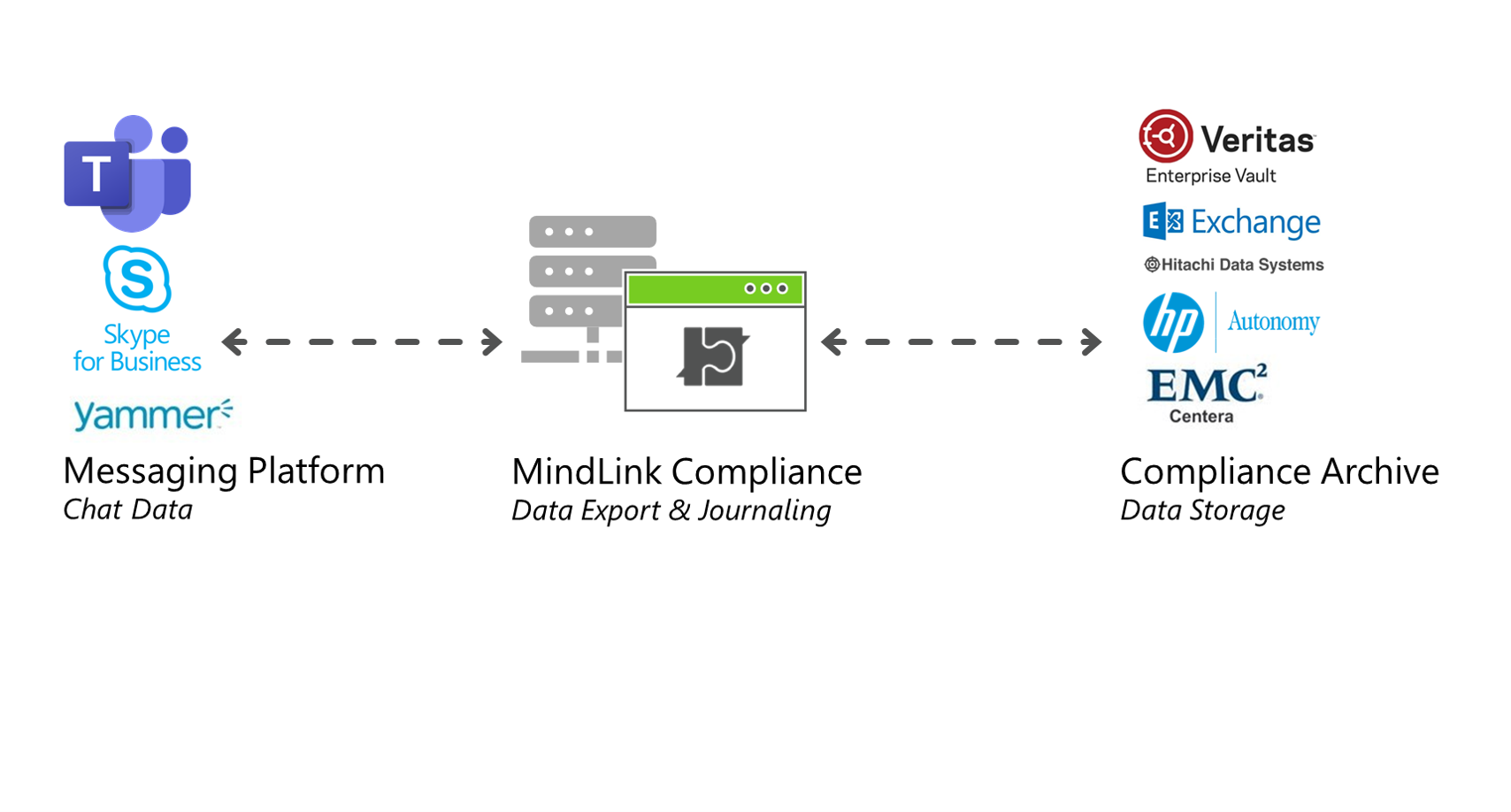

MindLink are pleased to announce Microsoft Teams integration for our MindLink Compliance solution.